The whirlwind life of legendary film enthusiast, professor, writer, photographer, filmmaker, and founder of the University Film Society ended Dec. 20, 2021 when Al Milgrom, 98, succumbed to a stroke.

Milgrom left behind a Twin Cities film scene that had been greatly influenced by his passion for film.

Milgrom taught film at the University of Minnesota and founded the U Film Society in the 1960s. In time his efforts produced what became the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Film Festival (MSPIFF).

Susan Smoluchowski, the current executive director of MSPIFF, recalls meeting Milgrom soon after she moved here 20 years ago. “A friend of mine invited me to the opening night of the film festival, so I went and that is where I first encountered Al,” she said. “Later, I learned a bit about the legend behind so much of it, and I became involved with the festival. I started going to Oak Street. There was some angst among the board of directors. Al was the artistic director, but nobody was running the organization. I worked closely with him, and admired his cinema all the more.”

Noting that Milgrom did not necessarily want to run the organization but curate films, Smoluchowski said she continued to interact with Milgrom through a complicated time, but they got through it.

“For the last few years, we have had a very congenial relationship, and he came up to the MSPIFF offices often, and he came to all of our films. Prior to that time, Al would watch a few minutes of one film and then go and watch another for a short time. He never sat through a film. But the past few years he did, and it was wonderful to see how much passion he had.

“He could be an irascible, complicated, difficult guy, but he also had a warmth to him and a curiosity. He was a fascinating person to be around,” she said.

Smoluchowski remembered that one of the last times Milgrom popped over to her office before the pandemic, he was very pumped up. Milgrom told her that Woody Allen had made a film that was opening the San Sebastian International Film Festival. “You have to go, Susan, and meet Woody Allen. You have to have your 15 minutes of fame,” Milgrom said.

“That was indicative of the enthusiasm he had for all things cinema and for all things about other cultures,” Smoluchowski said. In his last few years, Milgrom worked on films that he had first started shooting in the 60s and 70s, referring to himself as the “oldest emerging filmmaker.” Two of those completed films showed at MSPIFF.

“Because of the influence Al had on them when they were growing up, so many people’s lives were changed because of his passion. He was extremely important to people,” Smoluchowski said.

‘Al was honest’

One of those people is Hamline-Midway resident Michael Reano, a filmmaker and camera man. Although he did not meet Milgrom until the 80s and really got to know him after 2000, he considered Milgrom his “film father.”

“I had a film, the ‘Father/Son Work Tapes’ that I hoped MSPIFF would show in 2002,” Reano said, “But Al didn’t want to. Al was honest. If he didn’t like something, he let you know.”

Reano said he could get into deep conversations with Milgrom about film history. “I was impressed with his knowledge. I could name drop directors, and Al would have stories about them or had crossed paths with them.

“I got to know Al, started hanging out with him. I worked on his Czech film and did a little bit on ‘Dinkytown Uprising.’ I was second camera on his ‘Berryman’ film.”

Reano said working with Milgrom and spending time with him was fun. “I just loved his drive, and his making films in his 80s. Al was always sort of a father figure to me. And that knowledge! He could drive you crazy, but I really enjoyed working with him.”

Reano said he also liked going to the Walker and watching the Spirit Award-nominated films with him, and then go out afterwards. Because of the pandemic, the last time Reano saw him was at the Walker in February 2020.

“I remember his crazy driving. I was not comfortable driving in a car with him. He would speed, get pulled over and then talk his way out of it.” Milgrom drove up until the week before he passed away.

East European and Russian filmmakers were Milgrom’s favorites, and he brought many of them to MSPIFF. “He brought in films that you would never get a chance to see anywhere else,” Reano said. One of his favorites was Truffault’s “400 Blows.”

“He would go to Documentary Club, and socialize, and it was such a great experience to be with him. When you were with him, in those last couple of years before the pandemic, you never felt like you were hanging out with someone who was 96. He was still wanting to make films.”

The more he got to know him, the more he found out about Milgrom’s life experiences. “He was a journalist in WWII, met a Russian ballerina, filmed in Russia by himself.

“He was such a character. I used to compare him to Studs Terkel. Once my parents were gone, I was so glad I could have Al as a friend.”

‘A character, an icon,

a gentleman’

Twin Cities actress Helen Chorolec was a college student at the U of M when she first came across Milgrom as he was showing films at the Bell Auditorium. She recalled going with her parents as a little girl to see Russian films on Sundays, and hearing about him then.

But it was about 15 years ago at the MSPIFF festival that she really got to know him. She was attending the festival with her mother, Olga, and she recognized Al with his glasses, beret and white hair.

“My mom and I were chatting in Ukrainian,” said Chorolec, “and Al came over and started to talk with us, using some Ukrainian phrases. He was of Ukrainian descent.”

She said her family had been refugees from Nazism, and Milgrom had a fascination with WWII history, so they had a lot to talk about. “He had to go somewhere else, but then he turned around and came back and gave us a handful of complimentary tickets. We were going to the films anyway, but whenever he saw us he gave us tickets, so we went to three or four films a day.”

She recalled, “We started to get to know these people, kind of a traveling gang that went to all these films you couldn’t see anywhere else, like a film about Finnish female resistance fighters who were captured by the Germans. These films were harrowing and difficult to watch, but wonderful films that resonated with me a lot.”

Chorolec said she and her mom would go to films and then to after parties, talking more with Al. “It was a wonderful time. I got to meet some of the European directors he brought over. Al was so generous. Even though he may have had a reputation as being cantankerous, he was super kind to me and my mom.”

She remembers Milgrom as being extremely independent, always on the go from one event to another. “He was always going to a film or to a lecture.

“He was also a flirt,” Chorolec recalled. “He would always ask me if I could find a good Ukrainian lady for him. He said he wanted to date someone around my age, who was vibrant and would want to go to concerts and films.

“Al hand-selected those European films for the festival. I was amazed at his stamina. Al was a character, an icon and a real gentleman.”

‘He was an improviser’

Mike Rivard, filmmaker and musician, said he shared shooting with Milgrom 12 to 15 years ago. “When I was a teacher at UC Video, located in an old church on the East Bank, Al moved the film society offices into that same church. I was his cameraman, and we started shooting for his current docs, a lot for ‘Dinkytown’ and a lot for ‘Berryman.’” John Berryman was a professor at the U who committed suicide, and Milgrom wanted to do a film on him.

“For his Berryman project, he found a couple of experts on Berryman, and one of them was a professor at a college in Boston. Al made the arrangements, and we flew out to Boston.”

Rivard said Milgrom was an inveterate note taker, and when they were getting on the plane, he had about six bags of legal pads, a camera bag, and bags of books, all on a wheelie cart. “Halfway down the aisle, the cart tips. I was behind Al and could help him scoop all this stuff up. Anybody who knew Al could just picture this.”

Once they got to Boston, they met with the professor, which Al had said would take about an hour. An hour passed, and the interview had not even started, so the process was closer to three hours.

“We were setting up lights and mics as we walked through the library. Of course, Al had no permission to do this. He was an improviser. He used to say ‘We’ll get there and make it happen.’”

He said the expert on Berryman became totally engaged with Milgrom, and realized that he knew his stuff. And things turned around, and the professor began interviewing Milgrom, and they went on for hours.

“Al educated several generations of people who went on to become filmmakers themselves. The Cohen Brothers made a reference to him in their film, ‘Inside Llewyn Davis.’ He also influenced Werner Herzog. Al was known around the world to a certain generation of filmmakers.”

‘Nothing could stop him’

Artist and photographer Janet Bayliss would see Milgrom off and on over the years, when she was a student at the U, attended foreign films and worked in Dinkytown. And over the years, those occasional meetings increased, and she became a close friend.

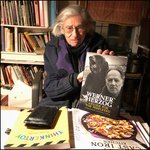

Reflecting on Milgrom, she said he lived in a house of books. “He was a voracious reader of everything,” she noted. “If you came to his house early to pick him up for a shooting, he would be in his kitchen drinking a cup of coffee with cream and poring over the New York Times.

“He read the New York Times religiously, and he would tell me when he saw someone he knew from the past had died.”

Bayliss talked about driving in Dinkytown with Milgrom. “He yelled stop and jumped out of the car. He had found his Berryman, someone he wanted to re-enact in his film, and he wanted photos of him and got all his information. Then he recognized a street person he knew, and he gave him a couple of dollars. Then he saw a young lady with a puppy, and he ran across the street to pet the pup-py.”

She said Milgrom would go to the Walker, to the Guthrie, to the library, the Y, the bookstore. He loved to go dancing. When he died, he was working on his film of Russia.

“The saddest thing for me to see after he died was his kitchen calendar. Al loved calendars, and he had them all over and would give them as presents. His calendar was always over-filled with events he was going to. And I looked at the month of December, and he only had two entries.

“COVID-19 was really hard on him,” Bayliss said, preventing him from going places. “He was so used to going out to pick up one ingredient for an Italian stew he was making.”

Bayliss recalled that when Milgrom was 96, they were up near Pine River and he wanted to shoot a scene for one of his films from the water to the shore. He found a paddle boat, and they went out in the boat to make the shot. “Nothing could stop him,” she said.

Agreeing with others who knew him that Milgrom was always taking notes, Bayliss commented that his notetaking is complete.

“There are people who touch your soul like no other.… They’ve taught you so much about life that their disappearance is unfathomable.… Al was one such person.”

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here